The Tears of Wild Birds

The Tears of Wild Birds

Beginning in early February when the morning temperatures were still in the 20’s, they brought sticks and kept adding more as the first ones fell through the outdoor wall sconce. By the end of the month, I could pick up a handful of twigs and small feathers about twice a day from beneath the same lighting fixture near the front door. Remembering a small house attached to the back fence, I removed it to a place under the same entry portal hoping that it might be a more successful location for them. After a day or two the two tiny house sparrows decided to build in the new spot, but instead of inside they made a small nest on top where there was a small shelf, the roof of the actual birdhouse. Success, after a fashion.

Every time we left the house the female would rush out of the nest and fly to the nearby juniper trees. This seemed unavoidable although we occasionally would use the back door just to be less intrusive. My limited understanding of these birds recalls that they like being around people, though these two seemed to want distance despite their insistent choice for their nest under our front portal.

It was either the gusty spring winds, or the constant fleeing from the nest, and one day on the brick walkway beneath the new nest a tiny blue, broken egg. No sign of either of the house sparrows then and since.

How does a tiny creature like this react to losing the potential fledgling? What happened when the little blue egg came crashing down? It would have only taken an instant and perhaps the wind rolled it out when the mother wasn’t even there. The only record was the broken egg and that night a rain shower washed most of it away. They never returned.

We anthropomorphize animals all the time, from short stories to Disney films. The emotional landscapes in these tales mirror our own and no attempt is made to bring anything new to animal psychology in these contexts. Still, after watching all this energy and effort to make a nest for one tiny blue egg and then have it all destroyed in the blink of an eye, one wonders that there must be an emotional reaction that we do not have receptors for, nor perhaps experience of despite the tendency to anthropomorphize the creatures that live around us. Our receptors for this sort of thing are so filtered by our own experiences and the human stories we create and absorb that we cannot easily begin to unfold new, different assignations for the emotions of these small birds, for example.

This isn’t necessarily a failing on our part, but it does create yet another gap between humanity and the natural world that is at best mysterious and at the worst, a kind of conditioning that impoverishes us. We have since Aristotle and Linnaeus brought our own systems to bear on how we see and so catalogue nature. There have been a variety of agendas at work in these and most of the efforts since seem to reinforce our claim to superiority which has increased this gap we foster.

Adam was tasked in Genesis with naming the plants and animals in the Garden of Eden and so we see the name before we begin to encounter the actual. Paul Valery’s: “Seeing is forgetting the name of the thing one sees” presents itself as a kind of shield or antidote to the catalogue and the gap we have invented for the rest of the natural world. This might also be extended to the hidden emotional life of the other than human world.

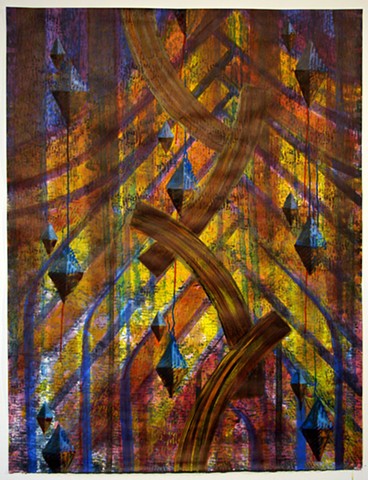

These paintings are my reactions to what is discussed above and there is a concerted effort in them to avoid representing “birds” in any immediately recognizable details. Instead movement, spatial environment and atmosphere via color harmonies attempt to set the stage for a meditation on the emotional life of two small birds who have created and then lost the potential to foster one of their own in a world we share with them.