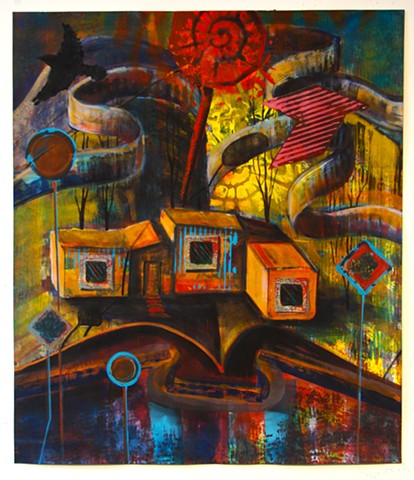

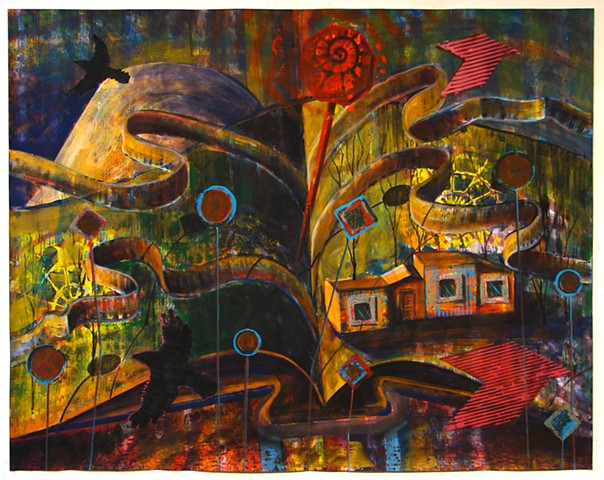

Lived Cover to Cover Beside a Heavy Hill

Lived Cover to Cover beside a Heavy Hill

There was a hill behind the house I grew up in which was wooded and had at least two very old oak trees that could shield the summer sun rising behind them until almost noon. It’s probably a very rare case these days for anyone to live their entire life – from cover to cover – in the same house. While my mother lived in the same house from young adulthood until she had a stroke and could no longer be there alone, by that time she had spent decades watching the sun rise through the wooded hill. Having spent my entire childhood there until I left home for college at eighteen, the hill was a mysterious place that seemed to go from a massive and varied landscape to one that eventually had one short path across it that switch-backed once to the top. The oldest oak trees eventually fell down so their majestic height was also taken away from the scale of the hill.

That was all either when I lived there or not too long after I’d moved away. So now when I think of the hill it seems to have a different scale altogether, a scale in time and a place in the past. I know that the hill still sits behind the new person’s house on the same street and that the small brick house would look mostly the same if one were to drive by it. For years, as well as today, there has never been any need or desire to visit the street again.

All of what went on in the rooms of that house for all the years that I either lived there or visited my parents there has a very different and vastly detailed history that would be pointless to try to document, but the hill that was always there is, of course, a different story. To describe it as a natural habitat or as a geological phenomenon in the north eastern United States in an area that was in the path of glaciers and the resulting mountains, all worn down significantly by now, is not really the kind of documentation I might find ultimately meaningful to me. I am not even painting a kind of landscape portrait of that particular hill or its surroundings either. So the science and history are not essential nor is any kind of nostalgia which I would agree usually functions as a kind of ‘second-hand emotion.’

In fact, creating a static image – a painting, that is – also doesn’t necessarily convey or cover the kind of scale of reminiscence that I would like to engage and then engage others with. Like the way an afterimage appears and then quickly retreats from view while still glittering its remnant across our consciousness, I also think of the hill as a broader biography or autobiography, in a sense, changed yet familiar.

Effective theatrical lighting can change what has become familiar for a time after the curtain opens into something that seems to be reemerging from what is on the stage that we were looking at but now have to recognize as something else, something that is still part of what we recall but also now has aspects, components, and a resonance that are new and different. Nothing has moved except the illumination used to change our perception. Two kinds of time seem to be at play here: there was, first the opening and our taking in what is presented and then there is the changes wrought by the effects of lighting and how we must reestablish our knowledge of the forms and their dispositions as they have become something else.

Light and color create one kind of movement in a painting, but there is always the viewer’s eyes roaming the picture plane and the variety of compositional devices that create a path and projected spatial circumstance that are also ways of guiding that movement. Since part of the subject matter in this painting is a book, reading and the back and forth scansion of reading is suggested and also interrupted by the part of the pages that are literally unraveling like pennants. So too, suggestions of the linear movement of air and wind carry the viewer back and forth at the same time that a depth is suggested beneath and above the book/landscape itself. The house sits on or just above the page of landscape in an immovable, solitary way.

This is all perhaps a depiction not of any specific memory but the quality and the sense of time that remembering occupies in our existence, especially when those memories are not just recalling what has been learned, but rather include the longer reach of personal experience that is layered in our minds and memory. We think back and can’t help but imagine alternate routes we might have pursued giving personal memory the judgmental review of hindsight. At the same time we try to excavate the kind of setting, its sensations of smell, humidity, atmosphere, in addition to the qualities of light and darkness, glare and shadow that might have been features of the places and time we are recalling and reforming in our minds.

While “Lived Cover to Cover Beside a Heavy Hill” does seem to address a specific biographical place and time the various markers – unreadable warning signs from the road seen from the back – the raven and its mechanical counterpart, the pitch of the landscape pages are all either intentionally vague or generalized so as to open out to the lives of those who are studying the picture. It is the act of remembering that we share as well as the commonalities of the landscape we inhabit. Like reading, and even in translation, there are ways that we can share our experiences and the memories that they have created. Paintings like this one are a kind of open ended storytelling where the narrative is intentionally an opening to be addressed, an invitation to bring oneself to the remembered portal revealed.