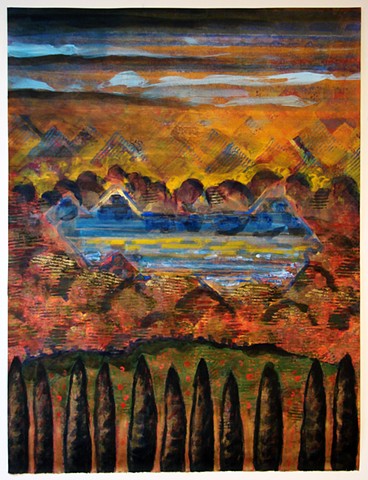

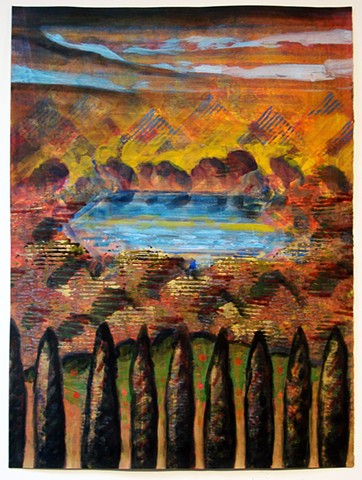

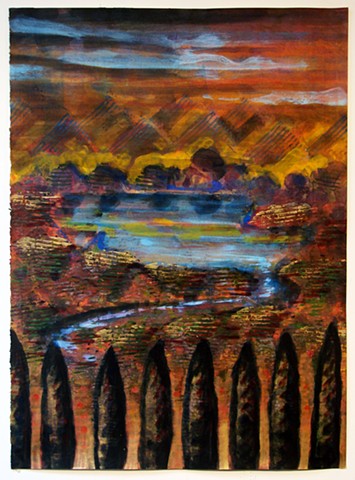

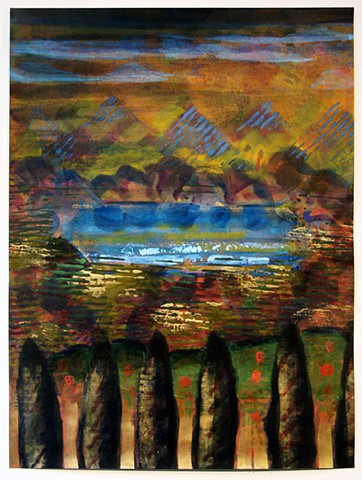

IDEALAND

IDEALAND – A Reinvention of Nature and Time

On the back side of Ohayo Mountain near Woodstock, NY, Clarence Schmidt built a rambling ‘house’ with grottos, rooms, and connecting passages that tumbled down the hillside towards the Ashokan Reservoir below. Built with salvaged materials of all sizes and description, from across the reservoir the multitude of windows sparkled among the trees they seemed embedded in. One night, after many years Schmidt’s ‘house’ caught fire and, since tar and timber were primary building materials, it burned to the ground. Not long after, Schmidt was moved into a nursing home in Kingston. With his long white beard and looking like a ghost of Walt Whitman, he would wave from the front porch, bundled up winter and summer in blankets or sweaters.

From my junior high school days on, the spirit and inventiveness of Clarence Schmidt was an ever-present influence that continued on into my undergraduate arts education at Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia and then as a graduate student in painting at Washington University in St. Louis. Going to art school had always been a foregone conclusion for me and the program of ideas about art and the world that are the basis for study there allowed me to begin to connect with the spirit and invention that continues today in my studio practice. Continually informing the initiative of making things – paintings and later music, too in my case – this spirit of ideas has been a sustaining force.

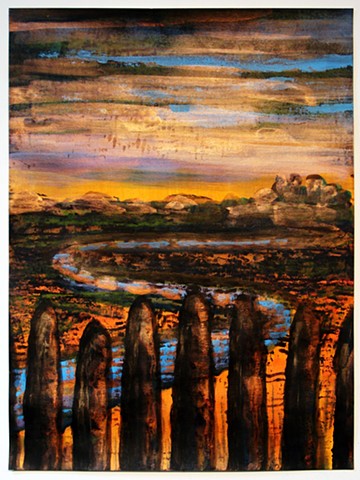

Without intending to, the paintings of “IDEALAND” are less about California’s landscape where I lived for much of my adult life, or about the New Mexican desert near Santa Fe where we live in now. Instead, the imagery in these paintings is more about the Catskill mountain environment where I grew up. They are a panorama of time. The present is represented by the hours working in my studio, the place where the ideas about these landscapes were invented and their composition took place. Then, ranging back from the present towards the rolling Catskill Mountains and the thick forests of oak, maple, white pine and hemlock, these paintings encompass decades and position one at an Arcadian-like viewpoint. This might be a vista we are sharing with Clarence as he looks from another side of the Reservoir, back across the inventories of memory.

The kind of mnemonic vista represented by ideas of landscape – rather than merely their photo-like reproduction in a painting – is one that I think we all share. It is a common ground of imagination where the idea of invention, not just nostalgia, formulates the desire to recall and reform the landscapes we have lived in. As we practice it as artists, or witness it as spectators, this inventive recall of beauty and depth of feelings continues to give us a path towards understanding ourselves and the world around us during the course of our lives.