Utility of Reflection

“Art is an alternative form of existence, though the emphasis in this statement falls on the word “existence”, the creative process being neither an escape from reality nor a sublimation of it.”

Joseph Brodsky from “Pendulum’s Song” - an essay on Cavafy

Reflection is a tool or device and is an undeniable part of our thinking about almost anything. We use our faculty of recall to remember and cast our thoughts backwards in time. We reflect and some reflections inevitably result in yearning or nostalgia, since time runs forward despite our mental exercises in reflection. The creative process makes constant use of reflection as the thought processes and mechanical processes of making something move forward in time. Two visual artists whose work and ideas I have always admired and respected put it this way:

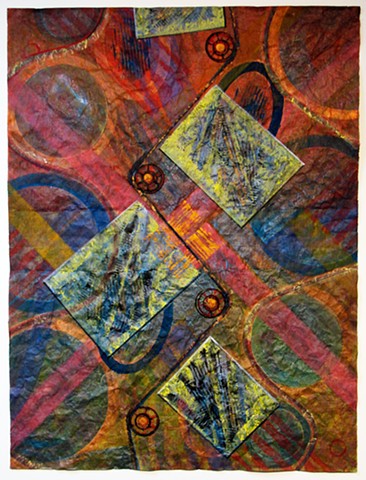

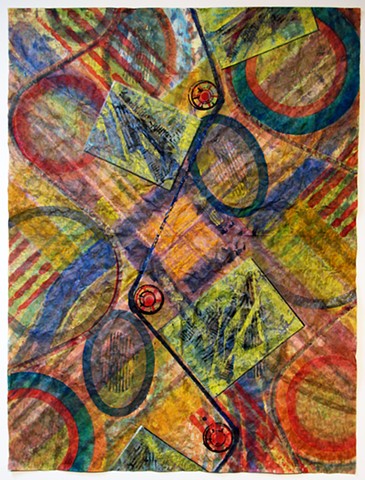

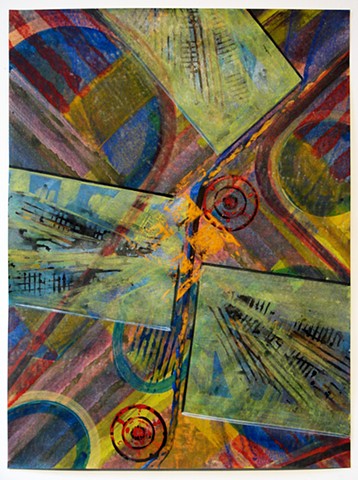

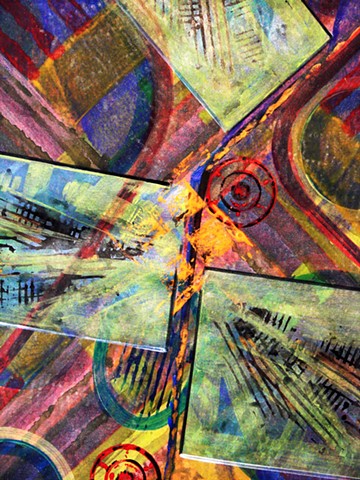

Jasper Johns: “Take an object. Do something to it. Do something else to it.”

Richard Diebenkorn: “There is nothing I cannot paint over.”

“I can never accomplish what I want – only what I would have

wanted had I thought of it beforehand.”

In both artists, the time between making the first move and subsequent reactions to it is that time spent reflecting on what has been accomplished so far and what needs to happen next. Composing each step in reaction to what has taken place before it is reflexive and makes creative progress the thoughtful and hopefully unifying program or presentation that it eventually might become. It is a process that requires total involvement in what came before, mentally, then what shapes an idea into the required form, and finally repeating these steps, doubling back again and again until a degree of completion finishes the thought in its new form. And so, as Brodsky suggests, the creative process is surely a part of existence and not a sublimation of it. Reflection used in this process is not an escape towards nostalgia, but a focused recall that allows for the manipulation of parts of the past into the forms at hand in the present.

In another sense, reflection may pose a relentless illusion. Consider how the condition of reverie as a means of meditating on something we might recall has a way of polishing the mirror. The way reverie makes the act of reflection an almost candy-coated reward that relinquishes only the vaguest aspects of memory slowed down to a relaxed golden largo of sorts and with all the pleasing filters in place, makes it difficult to utilize the recall delivered from reverie. Only good news makes it across the threshold and while this may be beneficial on some levels it seems highly unreliable used in any further contexts.

Reflection then, needs to have an accompanying active awareness that can amplify without the distorting tempos of meditation. Painting is one method and music another that come to my mind. Both can make deliberate use of reflection albeit at different rates since by their relationship to time: painting perhaps allowing for a slower tempo than music in its performance mode. In both there is possibility for the kind of creative dialogue that Johns and Diebenkorn described above.

Another familiar form of recall is nostalgia, referred to by one writer as “a second-hand emotion”, which renders it on a par with reverie in terms of its limited usefulness. The difference between nostalgia and recall might be like the different temperament of the Romantic versus the Pragmatist or Scientist, perhaps. Both, however, represent forms of reflection and neither can be gauged objectively against the philosophy of Utilitarianism, bringing to mind a lingering question: how might reflection – personal work undertaken by an individual – square up against the utilitarian quest for happiness or, at the very least, an attempt at the maximization of well-being?

Since I believe that reflection is undertaken as an active awareness, unlike one of the tenets of Buddhism that pursues the negation of suffering where consequently a passivity may accompany that quest, using reflection to arrive at useful, sometimes painful reassessments of our path in life challenges us to step beyond passive reflection and find ways to utilize this backward glance or mirror image of ourselves now. Unsettling perhaps, a stubborn progressive advance can create states of discomfort as we realign ourselves, challenged by what reflection has brought to the surface. Taking the concerns of the utilitarian with us, is it really worthwhile to subject ourselves to that which is hidden in the surfaces of reflection?

Language and its link to memory are a foundation for our use of reflection. I am guessing that language seems to have come about as part necessity and part the urge to invent something. Its necessity might be related to the creation of signs, the guideposts we want to use to help ourselves and others find our way, often back to someplace already visited, for example. Where was the source for water, or where did the herds cross the river each spring? In addition to the necessity we might ascribe to language, our homo sapiens mind seems to have required some way to dramatize the passing of time, creating storytelling in its first forms. The basis for relating the past has always been recalling and then relating the remembered content in new, mnemonic ways. We invented an archive with language, and the way we continue to create in visual, musical and lexical forms is the continuing by-product of this invention. Its utility, then lies in the timeless path that has been evolving for centuries, a path that tells us where we have been, speculating about where we are and where we might be going along the track of time, reflection’s two-way mirror.